The ripple effect of a single newspaper article

Often, when navigating the canals, I fall down an unexpected rabbit-hole. I don’t mean stepping off the boat into a hole (which I have done), but mooring up and falling into a history paradigm. Sometimes the catalyst is a building or village, other times it’s something more random, like a tunnel. Usually the rabbit-hole is helped along by the primary sources of the British Newspaper Archive. Often leading me to see my surroundings through the words and experiences of those who went before, like the Blisworth Tunnel accident in 1861.

All of this is true of my experiences of the Blisworth Tunnel in Northamptonshire. This was the first canal tunnel I travelled through back in 2016. This broad, straight tunnel now causes me less stress, though my thoughts when inside are firmly located in 1861. The newspaper archives reveal a shocking accident in the tunnel leaving two men dead and two others seriously injured.

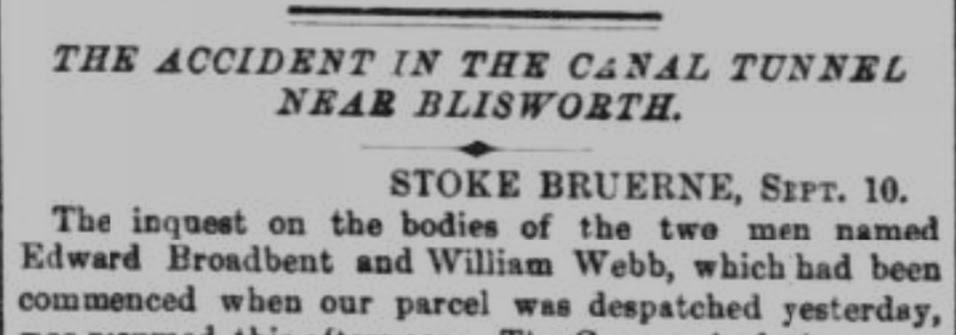

National reporting of a local event

So significant was the Blisworth Tunnel accident in 1861, it was reported in papers as far away as Ireland and Scotland1. However, not all accounts are equal and many of the press reports were inaccurate . For me the fascination isn’t some macabre fixation with the accident, but the unanswered questions that spring from reports. For instance, the lasting impact on the wives, children and communities left behind and questions relating to the reporting itself. I often find it’s what is not reported that leaves the biggest legacy.

The background -Blisworth Tunnel

Blisworth tunnel is the 3rd longest, navigable tunnel on the English canal network, joining the villages of Blisworth and Stoke Bruerne on the Grand Union Canal. Dug by hand the tunnel finally opened to boats in 18052. Opened with a single air-shaft, the lack of airflow didn’t matter quite so much to the engineless boats of 1805. In the early years boats were ‘legged3‘ through the tunnel, as horses were led over the top. But, the importance of the air-shafts did become an issue with the arrival of steam powered boats in late 1860.

New innovations – steam boats

Today, It is hard to imagine the change steam engines brought to canal boats. On a practical level carrying companies could try and compete with the expanding railway system. For the crews, engines brought a skills, sensory and physical shift. Practically, crewmen needed to be engineers alongside shoveling coal and living with the dirt and smell of the engine, plus the toxic fumes. The advent of steam on the canals brought a new era of engines and the beginnings of an hundred year shift away from horse-drawn boats. First introduced in November 1860 the Grand Junction Canal Company (GJCC) quickly added steam boats to its fleet.

Steam boat Bee

One of the new GJCC’s steam-driven boats was named Bee. Built of wrought iron, Bee ran from Birmingham to London with a 4 man crew. Two responsible for the engine, the others for steering the boats, as Bee also towed an engineless butty. One of Bee’s engineers had only recently joined GJCC having spent 9 years working on railway steam engines. It seems an unexpected turn that workers left the ‘new’ railway to work on the older canal network. The crew men left their wives at home onland, caring for children, and were often away for weeks at a time; an element of social history that hasn’t been interrogated. Bee’s early September journey had started a few days earlier.

Bee left London on Saturday 31st August and reached Birmingham on Wednesday, leaving for a return to London on the same day. By the evening of Friday 6th September 1861, Bee entered Blisworth tunnel on its run south, towards Stoke Bruerne. But, by the time the boat emerged into the village two men were dead and two others badly injured.

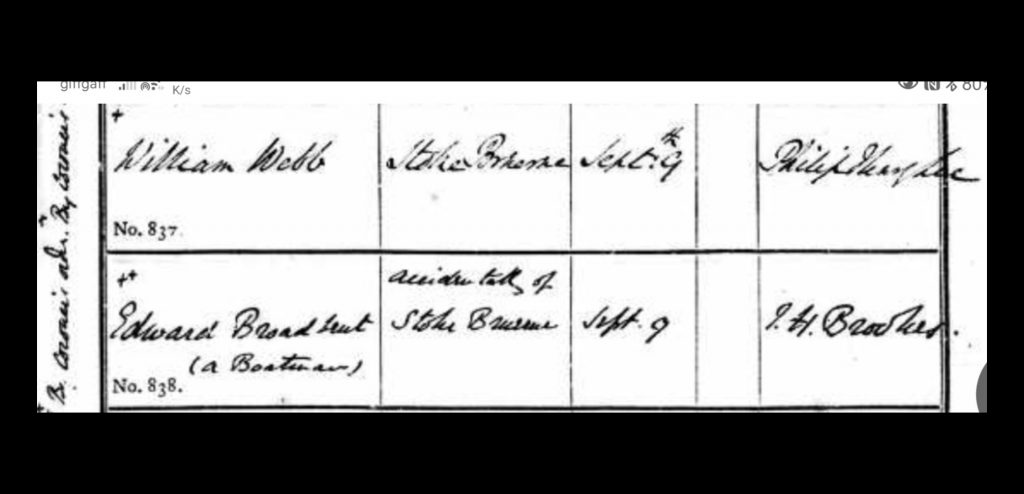

Slow reporting and a speedy inquest

First reports of the Blisworth Tunnel accident appear in a range of local papers on Tuesday 10th September4. By today’s instant news standards this seems an excruciatingly slow reporting of events. However, many newspapers were reliant on trains, stage-coaches and those travelling to get copy to the office. Additionally, the inquest into the accident didn’t start until Monday 9th. The reporter from the Morning Advertiser noted he left the inquest early to meet the print deadline. Although reporting seems slow, the pace of holding the inquest is quite the opposite.

Taking place on Monday 9th, less than three days after the accident, the fast convening of the inquest is striking. Locally, The Northampton Mercury printed the entire inquest in its Saturday 14th September edition, with additional observations from the reporter. The witnesses were questioned by the coroner, five men from the GJCC, the chair of the jury and a solicitor acting on behalf of the dead men’s families. The two page report, offers a glimpse into the working lives and social strata of the mid-19th Century. It also reveals a lack of the empathy, that today seems shocking, but the speed at which the inquest occurs gives an immediacy to those who survived the accident and witness accounts.

Through the witnesses’ eyes

Those interviewed reveal the confusion inside the tunnel and the wider experiences of those on board Bee. Enroute from Long Buckby, Bee’s engine had been struggling to reach full steam. Joseph Jones, engine driver and second engineer William Gower worked to clean the fire before entering the tunnel. Once inside Bee reached an area called the ‘stanks’ where a group of company men were working on a platform. One of these men, William Webb, a carpenter, cadged a ride, wanting to return to the village to sharpen his work tools. It was only once past the ‘stanks’ that the problems started and smoke began to fill the tunnel.

A leggers perspective

Travelling from the other direction, Joseph Wickens, a legger was working a horseboat through the tunnel. He described the smoke filling the tunnel and his boat becoming entangled in Bee’s butty rope. Calling out to Bee for help, Wickens received no reply, and in the thick smoke he couldn’t see any crew. Somehow the boats were unravelled and Bee’s butty was cast adrift. By this stage the smoke was so overwhelming Wickens and other crew couldn’t continue legging until the air cleared. Also travelling towards Blisworth was a second GJCC steam boat and butty, named Wasp. Wasp was travelling behind the boat Wickens was legging, creating more smoke inside the tunnel.

Onboard Bee

Onboard Bee the situation was already dire as Wickens’ boat came alongside. The two engineers onboard, Joseph Jones and William Gower had both passed out. Jones, who was controlling the engine had called to Gower to take over, but before he could help, both men became unconscious and were seriously burnt as they fell to the floor.

Of Bee’s other crew, Edward Broadbent was steering through the tunnel, with the second man, John Chambers, off duty sleeping in the hold and oblivious to the incident unfurling around him. However, William Webb, the local carpenter, was also travelling in the hold and stumbled onto Chambers waking him. Webb told Chambers one of the engine drivers had collapsed, and as Chambers went to help the engineers, Webb also became overcome by the smoke. Chambers tried to help Jones and Gower, but he too was quickly overcome by smoke and fell into the canal.

Emerging at Stoke Bruerne

Miraculously, after hitting the water Chambers came round and managed to clamber back onboard Bee as the boat emerged from the tunnel. Turning off the steam he found Gower and Jones collapsed and injured, Webb dead or dying in the hold and no sign of Edward Broadbent. Once back inside the boat Chambers also passed out and was only roused once the boat reached the top lock.

It is unclear how Bee reached the lock but as the boat left the tunnel a local man, John Sturges, was herding cows along the towpath. Sturges described the boat as full of smoke, not being steered and heading into the bank. He also claimed Chambers fell into the canal as the boat left the tunnel, in contradiction to Chambers’ own testimony. Once at the lock another villager, William Tew, a shoemaker, was the first to board Bee where he found the dead and injured. Back at the tunnel it took a further two hours of dragging the canal before Edward Broadbent’s body was found.

Injured and missing witnesses

The interviewing of witnesses reveals Victorian concepts of social status. Working class men were referred to only by name, in contrast to surgeons, canal company directors and others who were given the status of mister. Most striking, are the interviews with engineers Jones and Gower who had sustained serious injuries. After the accident they were taken to the Boat Inn, where beds were made-up on the floor. At the inquest the reporter described both men as unable to sit or stand. Additionally, Gower was powerless to lift a bible to swear an oath, as his hands were so badly burnt. But not everyone present during the accident was interviewed.

Missing witnesses

Bee survivors, leggers and other local men were all interviewed at the inquest but there were absences. Most notably no crew from the other boats passing through the tunnel gave testimony. Wasp, the other GJCC steamboat continued its journey, despite passing Bee at the height of the incident. It is difficult to know exactly why this was, however with a heavy GJCC presence at the inquest perhaps the pressure of paying shareholders outweighed the need for the coroner to call all witnesses.

Similarly, no crew from the boat Wickens was legging were called, nor any men working on the ‘stanks’. Finally, the families of the dead are also missing, not mentioned by name, nor apparently present in person. Notably Jane Broadbent and Ann Webb, the wives of the dead men. Though as Edward Broadbent and William Webb were buried on the day of the inquest their widows may not have wanted nor been invited to attend.

Jane Broadbent and Ann Webb – invisible victims of the Blisworth Tunnel accident

Jane Broadbent and Ann Webb may not have been physically present during the Blisworth Tunnel accident, but the impact on them was life changing. During the inquest Anderson, chair of the GJCC declared the bereaved families would be supported. However, it seems Jane and Ann each received a single payment of approximately a year’s salary and no subsequent support.

Jane Broadbent

Edward Broadbent’s wife, Jane, was 36 in September 1861. They had 8 children and the youngest, George, was only days old when Edward died. Jane was born in Braunston, Northamptonshire, and married there aged 20. She seems to have lived most of her life in the village, amongst other boat families, and her father had also been a boatman. Notably, on both the 1851 and 1861 census Jane was a lone parent, as Edward was away working. It is unclear whether Jane was present at the burial of her husband at Stoke Bruerne, it would have been a long journey with a newborn baby from her new home in Birmingham.

Moving to Birmingham

At some point, between April and September 1861, the Broadbent family had moved to Birmingham. Perhaps, meaning Jane would see more of her husband as he worked the new steam boats running to and from the city? For Jane the move must have been quite a shift, leaving behind Braunston and all the connections she had. After Edward’s death at the end of September 1861 the GJCC gave Jane a one off £45 payment. Although a substantial sum to receive, no further financial support was given to Jane and her 8 children by the GJCC.

Jane remained in Birmingham after Edward’s death until at least 1871. She appears there on the 1871 census living with one daughter, Sarah and her son-in-law. It seems Jane was living in a poorer area, as demonstrated by her neighbours’ all earning a wage as piece workers. Her youngest, surviving children, Jane (11) and George (9), were no longer living with their mother, but instead were working on a canal boat with Jane’s sister, Elizabeth, and her husband5.

The only other documentation I have found for Jane, comes in 1875. She then marries for a second time, to a man named James Miller, in Widnes, Lancashire. There is no way of tracing, how or when Jane met James. However, he was a waterman or boatman, so it is possible they met via other waterways workers. After that Jane drops from the historical record and I hope her second marriage, aged 44, brought her happiness and stability.

Ann Webb

Ann Webb was 39 when her carpenter husband, William Webb, died. According to the inquest Ann and William had only married the previous year, but despite my best efforts I have failed to find the marriage registration. It seems Ann was William’s second wife6, and they had no children. After William’s death it is difficult to know what immediately happened to Ann, like Jane she was given a payout by the GJCC, but clearly this wasn’t enough to live off forever.

By 1871 Ann was living in Bugbrooke, as a housekeeper to two young, single women aged 16 and 19. Over the next 10 years one of the women died, and the other married. However, Ann remained in Bugbrooke for the next 30 years, living alone or with her cousin, Elizabeth Murray, also a widow. Anne’s financial situation is described as ‘living on her own means’, implying she had her own money and didn’t rely on the parish. I find Ann to be an enigmatic figure, leaving behind so many unanswered questions. This is a frustratingly common experience when it comes to researching the lives and experiences of women.

The impact of the accident

Mis-reporting

Although the Northampton Mercury printed the full inquest, most others gave short accounts, often with multiple mistakes. The ripple effect of this is that more recent online articles have similarly repeated the errors of the 1861 reports. It became apparent when reviewing the newspapers that information was either taken out of context, made-up or not understood. Issues range from the mis-naming of William Webb to giving the wrong name to the main boat in the accident. William is often described as a ‘young man’ even though he was in his 40s7. Perhaps this mis-aging better fits a tragic narrative of a recently married man, leaving behind a presumed a young wife.8

Many of the accounts describe the GJCC steamboat Wasp as the boat with the problems, and miss out Bee completely. These accounts focus on boats becoming entangled, but confuse which boats this happened to. In some cases two steam boats are described, in others a legged boat and a steam boat. Most reports do not correctly identify the 5 boats in the tunnel. Notably, the incorrect accounts are very similar, even down to the headlines. All raising the question of whether this is a single, syndicated article, or whether journalistic plagiarism has taken place.

Inquest findings

The outcome of the inquest was that Edward Broadbent and William Webb died of asphyxiation9. The causes of the smoke were not properly identified, but it appears to have been a combination of issues. These included the wind blowing the smoke back towards the Bee as it travelled through the tunnel, further intensified by smoke from Wasp. Added to this the only air-shaft was partially covered over with a wooden hut, and there did seem to be an issue with either the coal being burnt or the engine onboard Bee. It should also be noted that the jury recommended the need for more air shafts in the tunnel. Today, there are seven air-vents, some as shafts from above, and others through the sides of the tunnel.

Finally

I always think accessing the British Newspaper Archives is like looking through a window onto past events. On the surface the reports give accounts of long forgotten people. However, multiple reports of one event when taken together reveal a more complex picture. Not just of the events in question, but also of reporting methods. The reporting of the Blisworth Tunnel accident, 1861, demonstrates the need to look beyond the newspapers for the experiences of others, most notably in this case, the women. Jane Broadbent and Ann Webb were both invisible victims of the accident and remained nameless both at the inquest and subsequent news reports, yet their lives were changed forever.

If you have enjoyed my research and writing please do consider ‘buying me a coffee’. A virtual coffee is just £3 and is always gratefully appreciated.

- The British Newspaper Archives shows over 150 articles published in Sept 1861 relating to the accident. ↩︎

- 1805 newspapers reveal the sale of equipment used in the building of the tunnel. ↩︎

- Legging was done by attaching boards or planks to the sides of boats, the planks stuck out from the boats like wings. Once in place men, or women, lay on the boards and then ‘walked’ their feet along tunnel walls or the roof, if it was low enough, so moving the boat through the tunnel. At Blisworth leggers were licensed by the GJCC. ↩︎

- First accounts I have found appeared in the Morning Advertiser, a London paper and the Dublin Evening Post, demonstrating the news worthiness of the accident and perhaps the ability to use telegraph communication to send the story from London to Dublin ↩︎

- At the time of the census George and Jane were at Great Haywood Wharf in Staffordshire. ↩︎

- William married Sara Watt in 1845 ↩︎

- It is difficult to know his exact age as he was born before the registration act of 1836. The 1861 census lists him as 49, whilst the 1851 census lists him as 30 and living in Berkhamstead. ↩︎

- Although the accounts mention William Webb was recently married, none mention that Ann was his second wife. ↩︎

- The surgeon at the inquest said Webb and Broadbent died in part to being older, unfit, and in his words, the ‘fattest men working for the company’. Additionally, the surgeon put Chamber’s survival down to his youth and fitness. ↩︎