Canals, hats and Atherstone

The Coventry Canal, winds its way from the centre of Coventry to Fradley Junction, where it meets the Trent and Mersey Canal. Along the way it passes through the small Warwickshire town of Atherstone. Atherstone is well known for its 300 year role in the manufacture and sale of hats. When the canal arrived, the Atherstone hat trade intersected with the new waterway.

The last hat factory closed its doors in 1999 and now stands derelict besides the canal. However, the town is proud of its heritage, as reflected in the bronze marker on the towpath opposite the remaining old factory. The memorial, which houses a tree growing thorough it’s centre has historical sculptured reliefs reflecting some of Atherstone’s past.

Parallel world of canal travel

In the summer of 2020 I moored opposite the deserted hat factory and next to the bronze memorial at Atherstone. I met lots of boaters and local people, as I traded from the boat in rare summer sunshine. Admittedly, I would probably never visit Atherstone if it wasn’t for the canal. Although only 38 miles from my house, it took the Pea Green boat a month to reach the town. As a result the extended travel time gave the illusion of journeying to the other side of the world.

Opposite the hat factory

Atherstone is a busy place to moor. Luckily, Mabel the Mooring Goddess was on my side. I niftily manoeuvred into the last spot before the locks. I was directly opposite the former Britannia works, also know as the Wilson and Stafford hat factory. A perfect spot for a few days of trading and meeting locals and boaters. This included the lovely folk and four legged friends onboard nb Wibbly Wobbly. Wibbly Wobbly is well worth looking out for. The boat is painted with fabulous Indigenous Australian art and Australian motifs. Also, as fellow traders they sell Mr Wippy ice-cream – which I had to taste test, a lot!

Hat talk in town

The old works of Wilson and Stafford are a talking point. On the towpath I met women who had worked in the factory at the time of its closure in 1999, and children of women who shared their mother’s stories of hat work in the mid 20th Century.

Long history of Atherstone hats

Of course, the history of hat manufacture in Atherstone pre-dates industrialisation. Atherstone’s soft water was essential in the felt making process and a reason why the town became hat central. Beginning as a domestic industry in the 17th Century, by the early 19th Century, work migrated from homes into factories. One of the earliest factories was located on Atherstone’s main road, Long Street. This early factory was established by Joseph Willday (sometimes spelt Wilday) in 1820. Willday came from a long line of hatters, and as we shall see was influential in the town . His Long Street factory pre-dated the Britannia works by a few years.

The Britannia hat works

The Britannia works is thought to have been built in the first half of the 19th Century. By then the Coventry canal had already opened. The remaining factory buildings are a hotch-potch of eras, early 19th Century structures fronting the road, and some more recent additions overlook the canal. My mooring was opposite a mixture of styles, including 1930s buildings with large metal framed windows reminiscent of Bauhaus modernism. Just below the windows alongside the canal are mooring rings. No-doubt when first built the factory’s location must have been handy. Not only for for receiving raw materials but also for getting finished hats onto boats for fast delivery to London or elsewhere.

Speedy canals

The suggestion of fast canal movement seems non-sensical, after all we perceive the canals as providing a slower pace of life. However, in the early 19th Century the canals provided a speedy delivery service across the network. More details of these canal schedules and routes can be found in historical trade directories.

Delving into the directories

Trade directories, first published in the late 1700s, initially covered large regions. Over time directories focused on individual counties, or just a single city. These fascinating books are a cross between a travel guide and a phone directory (though without phones). As well as transportation schedules they provide an insight into some of the people, trades and industries in each location. Alongside the town facts there is often a potted history. Today you can delve into many directories for free online. One of the earliest published directories covering Atherstone was published in 1828.

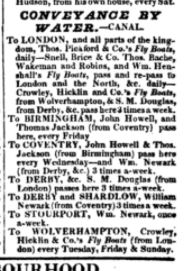

Boats that fly

Pigot and Co’s National Commercial Directory for 1828-29 covers every county in England and North Wales (sorry South Wales..). The entry for Atherstone includes schedules for canal boats, including fly boat services. Fly boats were the Amazon Prime delivery of their day. Often run by larger companies, they offered speedy, reliable delivery of goods, including perishable items. From Atherstone two companies ran daily boats to London. One was Pickfords, who by 1820 had perfected fly boat travel. Pickfords boats made the journey from Manchester to London by fly in an incredible 5 days, later cut to 70 hours.

Speeding up canal boats

Personally, given Pea Green’s pace and the months I take to get anywhere, I find the fly boat journey times staggering. Fly boats were, after all, still powered by horses towing the boat. However, Pickfords and other fly operators found ways to speed up the journey. For instance, horses were changed more frequently and fed using nose bags. As a result horses were eating on the hoof rather than stopping to graze. Additionally, the all male crew of three plus the captain worked in shifts, meaning boats could work 24 hours a day. Finally, many fly boats were lighter, with wooden hulls rather than steel. They also had a different bow shape to speed movement through the water.

Busy transit point

Pickfords ran the largest number of fly boats on the Coventry Canal. Additionally, in January 1810 they paid a night movement licence for 50 boats. However, London was not the only destination, for boats through Atherstone. Canal boats were also frequently serving Birmingham, Coventry, Derby, Shardlow, Stourport and Wolverhampton. These canal schedules sit alongside road haulage and carriages, suggesting Atherstone must have been a busy transit point in the 1820s.

Atherstone and its hat makers

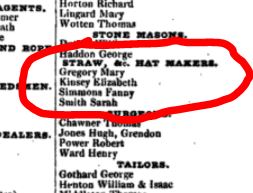

Atherstone also had a variety of shops and businesses in 1828. This included three different types of hat makers; hat manufacturers, milliners, and straw-hat makers. Interestingly the latter two categories of hatter were all female, whilst the ‘hat manufacturers’ were all male. This gendered division perhaps the result of societal norms of the time, which limited female access to banking and property ownership. Of the 7 hat manufacturers only two, Joseph Willday and John Power are identified as selling wholesale. Other directories do give clues as the type of hats being wholesaled.

Coarse hats

Francis Smith’s 1820 publication ‘Warwickshire Delineated’ mentions a ‘large quantity of coarse hats’ made at Atherstone. Although there is no description of the hats, ‘coarse’ implies cheap, roughly made items. Smith also suggests the ‘manufactory’ of hats employs a lot of town people. Directories published between 1835 and 1888 continues to reflect Atherstone’s reliance on hat manufacture. The directories don’t tell us where the hats were being sold, nor do they delve into times of social unrest . More evidence about where the hats in the late 18th and early 19th Centuries appears in 1845.

Role in the slave economy

The 1845 Kelly’s directory reveals changes to Willday’s business. Willday shifted his production to ‘the fine hat trade which, within the last few years, has superseded the felt hat trade, which was principally devoted to the supply of hats to slaves in the West Indies. Emancipation has given them more refined notions.’ This extract provides an important insight into early Victorian Britain. When viewed through through a 21st Century lens, it is difficult not to be disturbed by these comments.

Victorian attitudes

The 1845 Kelly’s provides a glimpse of the sprawling reach of Britain’s slave economy, via a throw-away comment. The network stretched way beyond Caribbean plantation owners, as the role of the Atherstone hat industry demonstrates. Also, the comments reveal something of the writer’s perceptions and attitudes in the years after the abolition of slavery in 1833. The writers deprecating reference to the ‘refined notions’ of the former slaves implies they had attitudes above their station. Though, the comment also reflects the writers Victorian attitudes to a person’s position in society. Of course, this comment fails to acknowledge or understand post-abolition conditions.

After the Abolition of Slavery Act became law in 1834 in most cases those enslaved became indentured workers – i.e. slaves but by another name. When finally freed in the late 1830s many former slaves endured extreme poverty. It was a time when the bottom fell out of the sugar industry and a wide reaching economic downturn took place. As a result, it is unlikely these people would buy expensive hats exported to the Caribbean from Atherstone.

Unanswered questions

Although Kelly’s 1845 directory provides a clue to the destination of some of Atherstone’s hats, there are many unanswered questions. For instance, the human networks behind the hats reaching the Caribbean. Who were the men and women who made, packed, ordered and shipped hats from Atherstone to plantations?

Of course, this type of historical information is both peripheral and ephemeral. Such papers are rare and if they have survived, are often accidentally part of larger manuscript bundles. Perhaps we will never know the answer to this question, but to understand Britain’s past, we should consider it.[1]The only referenced example, I have found online, of Atherstone hats sold to plantation owners to be worn by enslaved people appears in a PhD thesis by Chris Heaton. Joseph Willday’s … Continue reading

Street protests

Atherstone’s hat trade has definitely left me wondering about the early 19th Century in the town. After all the 1830s were a turbulent time across Britain and Atherstone was no exception to this. Joseph Willday, who also had offices in London,[2]A London trade directory lists Joseph Willday as having offices in Borough, close to the centre of London’s hat making in Bermondsey. and during the 1830s tried to challenge the hatter unions in Atherstone.

Willday, had friends in high places as a request for changes to union laws (known as the combination acts) was raised, on his behalf, in the House of Lords in April 1834. However, it seems Willday was unsuccessful in breaking the union. By June 1834 the town saw street protests against the hat manufacturer as Willday tried to take his best hat makers to Rugeley, so bypassing the union. Ultimately Willday was unsuccessful in changing the status quo. He died in 1852, whilst still living in Atherstone.

Atherstone and its hats in the future

My time at Atherstone was marked by meeting interesting people and making the most of the town’s amenities. I have since learnt more of the town’s complex history. Now, I am left wondering how Atherstone’s hat production and street protests would have sounded. Additionally, I also find it hard to marry this quiet market town with its innocuous colonial links. The last obvious remnant to the hat industry is the now derelict Wilson and Stafford factory, which may, at some point become housing for the elderly. How Atherstone remembers it’s hat industry and which bits it will choose to memorialise will be the new challenge.

| ↑1 | The only referenced example, I have found online, of Atherstone hats sold to plantation owners to be worn by enslaved people appears in a PhD thesis by Chris Heaton. Joseph Willday’s grandfather exported hats to America in the 1760s when the country was still a British colony. The hats were shipped through the port of Bristol to Philadelphia. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | A London trade directory lists Joseph Willday as having offices in Borough, close to the centre of London’s hat making in Bermondsey. |

What an interesting post – I hadn’t realised Atherstone was renowned for it’s hat making industry, or that the derelict building alongside the canal had been a hat making factory.

I find it intriguing when one can establish the original purpose of a building such as the ‘Britannia Works’. Looking through the ‘Historic Building Survey’ link and seeing the internal photos of the vast open spaces, one can’t help but to imagine the hat makers hard at work during it’s heyday. I understand the building is now planned to be redeveloped into canalside residential apartments.

Also I was fascinated to read the bit about the ‘fly boat service’ – again I hadn’t realised that this went on.

A great interesting read Kay, thank you.

Clive, as always thank you for reading and commenting.

Yes, the Leicester uni report on the Britannia works is really interesting. I tried to find the earlier report it mentions but so far have failed. Apparently there have been a number of failed attempts to develop the Britannia site, and now it is marked to become residential for the elderly. (Though the older bricks will have to be cleaned and reused as it is a listed building.)

Yes, the fly boats boggle my head. Apparently it meant different things in different places. So, in Scotland fly boats were described as having horses galloping along the towpath! I think this must have been a shipping canal with more towpath space. Can you imagine if they did that on the Leicester Line now? Hope you are well, Kay

Thank you Kay, absolutely fascinating. Appreciate your attention to detail and questioning. Living on a narrowboat since Nov 2020 I have become a hat fan. This article makes me more inquisitive about derelict industrial buildings and history of people and place. Wonderful.

Pip, thank you for taking the time to read and comment. Haha! Yes am totally with you over hats. I have always been a hat fan – as a red head I fry and freeze in equal measure. I had never really thought about where the hats were made though. Enjoy your boat. Kay

Thanks for the information about the hatters of Atherstone. We’ve moored a few times by the derelict factory and initially just thought it was a scruffy old place with broken windows! Now I know it’s interesting origins. I’ve got a feeling there was a fire near there recently (ish) so hopefully it will still be useable.

Thank you for reading and commenting. Yes, it’s such an interesting building and the history of the town is fascinating too. I think a lot of boaters just see it as an eyesore, and don’t understand its significance. You are right there was a fire, I am not sure what state it is in at the moment!

The building is am embarrassment to us town folk now. The front has collapsed, the footpath closed. The hope of the planning application for flats off open cobled walkways, a cafe by the canal with a hatting sculpture and a museum with gift shop fadded into history. My brother worked in the Veros hat factory in town for years. That too is looking sorry for itself.